#racist incarceration policies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Libs are like, "YOU CAN'T LET TRUMP WIN JUST BECAUSE BIDEN IS COMMITTING A GENOCIDE! THIS IS NOT THE TIME FOR SINGLE-ISSUE VOTERS", when the fact is that people are already really fucking angry at him for funding two wars during a severe cost of living crisis. Biden's pet dog has already gotten Israel and the US embroiled in a steadily escalating conflict with Houthis and Hezbollah in Syria and Lebanon, and now Netanyahu is trying to ethnically cleanse two million Gazans by pushing them out of the country into Egypt, one of the countries the US gives billions of aid money to make nice with Israel and help them trap the Palestinians. Egypt is already mad about this (although Idk what they expected lol) and if Israel creates a border conflict with them, Iran might press their advantage and then the whole region descend into an all-out war in which the US is embroiled. At which point oil prices will jump, the US economy get even worse, more tax money funnelled into TWO wars, one of which is due to the genocide.

People might not care about Muslims living thousands of miles away, but they have some very strong opinions about putting food on the table. At this point there's a pretty significant shift in the Black community towards Trump because Biden has INCREASED funding for police, is supporting Cop City that someone DIED protesting, and hasn't made a dent in mass incarceration (the marijuana pardon was fucking hilarious in a depraved way). The right has also been weaponizing Black people's resentment against Latino "illegal aliens" and Biden's "concessions" towards them, when actually his immigration policies have barely been less draconian than Trump's all this time. The reason he's making those concessions is that he has to look more progressive than him, except he's also been slowly escalating ICE crackdowns, keeping kids in cages and building a border wall. So the Latin voters are entirely fed up with him too.

So far, he's lost the Muslim vote, the Latin vote, the Black vote, the youth vote (people of ages 18 to 35 are the most outraged at the genocide in Gaza), and they're hemorrhaging the working class votes. These are the extremely angry and betrayed people the liberals are currently working overtime screaming at about Trump "bringing the death of democracy", like democracy means anything to them compared to losing jobs, money, visas, family members, health (Biden's first and ongoing genocide is disabled people due to his COVID policies), social infrastructure and money.

Y'all said Blue Not Matter Who and elected a career racist and known incompetent who supported segregation, was an architect of mass incarceration, got Clarence Thomas elected to the Supreme Court and spewed rhetoric against Arabs so genocidal that motherfucking Menachem Begin was like "....bro." And you got exactly what you paid for. If Trump gets on the ticket next year he's going to win, and no amount of screaming at people online is going to change that. So I suggest you start organising now. The age of trying to create a revolution at the ballot box is over.

#genocide joe#us politics#fuck trump#fuck the gop#fuck joe biden#white liberals#2024 elections#vote blue#vote blue no matter who#free palestine#anti blackness#black lives matter#immigration#ICE#police brutality#mass incarceration#current events#world news#fuck israel#knee of huss

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

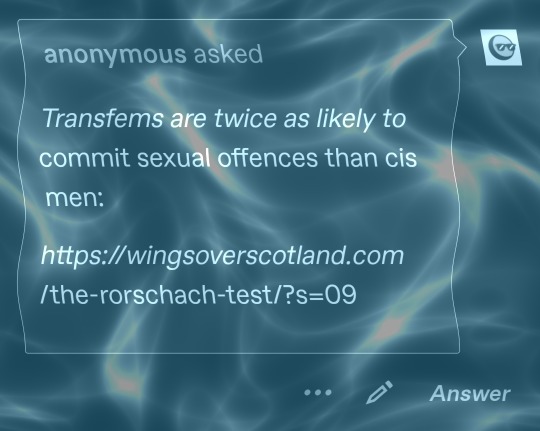

Firstly: get dunk'd, transphobe.

Secondly, nice source, dipshit:

I have to do everything, don't I?

Let's talk about this source before we even read this article, because it shows how poor your rhetorical analysis skills are - or how unwilling you are to practice those skills, or perhaps just how willing you are to ally yourself with racist, nationalist, far-right reactionaries if they also happen to be transphobic.

Wings Over Scotland is a far-right, nationalist, reactionary blog run by Scottish "video game journalist" Stuart Campbell. It is not an unbiased news website - it's some dude's personal blog, and he created it because he hated that mainstream news in Scotland wasn't spreading the far-right rhetoric he wished it would.

And this is what you used as a "source". Fucking laughable.

Now let's get into the actual blog post. I refuse to call it a "news article", because it's not. This one was written by a nobody named "Mar Vickers". At the bottom of the article, Stuart claims Mar has "extensive experience in equality law". I can't seem to find any indication Mar is some sort of lawyer or scholar; all I can find is a link to his twitter - sorry, I mean his "X":

https://twitter.com/mar2vickers

You can tell this is the same Mar based on the content of his tweets. He's also transphobic garbage, surprise surprise. He has a backup account on "gettr", because it seems like his twitter gets suspended frequently - which says a lot. Gettr is a clone of twitter that caters to right wingers who get suspended and banned on Twitter for constantly violating its hate speech policies. So. You know. Though these days, X is the safe-haven for far-right reactionaries, so honestly that's a red flag period.

As a summary: Mar doesn't understand surveys or their limits, he doesn't define what a "sex crime" is, he doesn't know what the Rorschach test is, and he's bad at math. He plays with numbers like he's some sort of population statistician, which he's not. He draws conclusions that are completely nonsense, because he's not asking the relevant questions.

Basically, he states that over the past few years, the ratio of trans women in jail for sex crimes to compared to the general population of trans woman is now higher than the ratio of cis men in jail for sex crimes compared to the general population of cis men. Ok, but why did these numbers change? He doesn't ask why. He just assumes these trends are natural and reflect the behavior of cis men and trans women, rather than the increased transphobia in England and Wales that he and his buddy Stuart have been fueling.

I absolutely don't doubt that trans women are incarcerated for "sex crimes" (which he never defines of course) at a higher rate per population than cis men. It's the same reason people of color are incarcerated more per population: bigotry. "Wow, this population of people who society hates sure gets sent to jail a lot. That's probably a reflection of their true nature, and not a reflection on society at large!"

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because senator Kamala Harris is a prosecutor and I am a felon, I have been following her political rise, with the same focus that my younger son tracks Steph Curry threes. Before it was in vogue to criticize prosecutors, my friends and I were exchanging tales of being railroaded by them. Shackled in oversized green jail scrubs, I listened to a prosecutor in a Fairfax County, Va., courtroom tell a judge that in one night I’d single-handedly changed suburban shopping forever. Everything the prosecutor said I did was true — I carried a pistol, carjacked a man, tried to rob two women. “He needs a long penitentiary sentence,” the prosecutor told the judge. I faced life in prison for carjacking the man. I pleaded guilty to that, to having a gun, to an attempted robbery. I was 16 years old. The old heads in prison would call me lucky for walking away with only a nine-year sentence.

I’d been locked up for about 15 months when I entered Virginia’s Southampton Correctional Center in 1998, the year I should have graduated from high school. In that prison, there were probably about a dozen other teenagers. Most of us had lengthy sentences — 30, 40, 50 years — all for violent felonies. Public talk of mass incarceration has centered on the war on drugs, wrongful convictions and Kafkaesque sentences for nonviolent charges, while circumventing the robberies, home invasions, murders and rape cases that brought us to prison.

The most difficult discussion to have about criminal-justice reform has always been about violence and accountability. You could release everyone from prison who currently has a drug offense and the United States would still outpace nearly every other country when it comes to incarceration. According to the Prison Policy Institute, of the nearly 1.3 million people incarcerated in state prisons, 183,000 are incarcerated for murder; 17,000 for manslaughter; 165,000 for sexual assault; 169,000 for robbery; and 136,000 for assault. That’s more than half of the state prison population.

When Harris decided to run for president, I thought the country might take the opportunity to grapple with the injustice of mass incarceration in a way that didn’t lose sight of what violence, and the sorrow it creates, does to families and communities. Instead, many progressives tried to turn the basic fact of Harris’s profession into an indictment against her. Shorthand for her career became: “She’s a cop,” meaning, her allegiance was with a system that conspires, through prison and policing, to harm Black people in America.

In the past decade or so, we have certainly seen ample evidence of how corrupt the system can be: Michelle Alexander’s best-selling book, “The New Jim Crow,” which argues that the war on drugs marked the return of America’s racist system of segregation and legal discrimination; Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us,” a series about the wrongful convictions of the Central Park Five, and her documentary “13th,” which delves into mass incarceration more broadly; and “Just Mercy,” a book by Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer, that has also been made into a film, chronicling his pursuit of justice for a man on death row, who is eventually exonerated. All of these describe the destructive force of prosecutors, giving a lot of run to the belief that anyone who works within a system responsible for such carnage warrants public shame.

My mother had an experience that gave her a different perspective on prosecutors — though I didn’t know about it until I came home from prison on March 4, 2005, when I was 24. That day, she sat me down and said, “I need to tell you something.” We were in her bedroom in the townhouse in Suitland, Md., that had been my childhood home, where as a kid she’d call me to bring her a glass of water. I expected her to tell me that despite my years in prison, everything was good now. But instead she told me about something that happened nearly a decade earlier, just weeks after my arrest. She left for work before the sun rose, as she always did, heading to the federal agency that had employed her my entire life. She stood at a bus stop 100 feet from my high school, awaiting the bus that would take her to the train that would take her to a stop near her job in the nation’s capital. But on that morning, a man yanked her into a secluded space, placed a gun to her head and raped her. When she could escape, she ran wildly into the 6 a.m. traffic.

My mother’s words turned me into a mumbling and incoherent mess, unable to grasp how this could have happened to her. I knew she kept this secret to protect me. I turned to Google and searched the word “rape” along with my hometown and was wrecked by the violence against women that I found. My mother told me her rapist was a Black man. And I thought he should spend the rest of his years staring at the pockmarked walls of prison cells that I knew so well.

The prosecutor’s job, unlike the defense attorney’s or judge’s, is to do justice. What does that mean when you are asked by some to dole out retribution measured in years served, but blamed by others for the damage incarceration can do? The outrage at this country’s criminal-justice system is loud today, but it hasn’t led us to develop better ways of confronting my mother’s world from nearly a quarter-century ago: weekends visiting her son in a prison in Virginia; weekdays attending the trial of the man who sexually assaulted her.

We said goodbye to my grandmother in the same Baptist church that, in June 2019, Senator Kamala Harris, still pursuing the Democratic nomination for president, went to give a major speech about why she became a prosecutor. I hadn’t been inside Brookland Baptist Church for a decade, and returning reminded me of Grandma Mary and the eight years of letters she mailed to me in prison. The occasion for Harris’s speech was the annual Freedom Fund dinner of the South Carolina State Conference of the N.A.A.C.P. The evening began with the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and at the opening chord nearly everyone in the room stood. There to write about the senator, I had been standing already and mouthed the words of the first verse before realizing I’d never sung any further.

Each table in the banquet hall was filled with folks dressed in their Sunday best. Servers brought plates of food and pitchers of iced tea to the tables. Nearly everyone was Black. The room was too loud for me to do more than crouch beside guests at their tables and scribble notes about why they attended. Speakers talked about the chapter’s long history in the civil rights movement. One called for the current generation of young rappers to tell a different story about sacrifice. The youngest speaker of the night said he just wanted to be safe. I didn’t hear anyone mention mass incarceration. And I knew in a different decade, my grandmother might have been in that audience, taking in the same arguments about personal agency and responsibility, all the while wondering why her grandbaby was still locked away. If Harris couldn’t persuade that audience that her experiences as a Black woman in America justified her decision to become a prosecutor, I knew there were few people in this country who could be moved.

Describing her upbringing in a family of civil rights activists, Harris argued that the ongoing struggle for equality needed to include both prosecuting criminal defendants who had victimized Black people and protecting the rights of Black criminal defendants. “I was cleareyed that prosecutors were largely not people who looked like me,” she said. This mattered for Harris because of the “prosecutors that refused to seat Black jurors, refused to prosecute lynchings, disproportionately condemned young Black men to death row and looked the other way in the face of police brutality.” When she became a prosecutor in 1990, she was one of only a handful of Black people in her office. When she was elected district attorney of San Francisco in 2003, she recalled, she was one of just three Black D.A.s nationwide. And when she was elected California attorney general in 2010, there were no other Black attorneys general in the country. At these words, the crowd around me clapped. “I knew the unilateral power that prosecutors had with the stroke of a pen to make a decision about someone else’s life or death,” she said.

Harris offered a pair of stories as evidence of the importance of a Black woman’s doing this work. Once, ear hustling, she listened to colleagues discussing ways to prove criminal defendants were gang-affiliated. If a racial-profiling manual existed, their signals would certainly be included: baggy pants, the place of arrest and the rap music blaring from vehicles. She said that she’d told her colleagues: “So, you know that neighborhood you were talking about? Well, I got family members and friends who live in that neighborhood. You know the way you were talking about how folks were dressed? Well, that’s actually stylish in my community.” She continued: “You know that music you were talking about? Well, I got a tape of that music in my car right now.”

The second example was about the mothers of murdered children. She told the audience about the women who had come to her office when she was San Francisco’s D.A. — women who wanted to speak with her, and her alone, about their sons. “The mothers came, I believe, because they knew I would see them,” Harris said. “And I mean literally see them. See their grief. See their anguish.” They complained to Harris that the police were not investigating. “My son is being treated like a statistic,” they would say. Everyone in that Southern Baptist church knew that the mothers and their dead sons were Black. Harris outlined the classic dilemma of Black people in this country: being simultaneously overpoliced and underprotected. Harris told the audience that all communities deserved to be safe.

Among the guests in the room that night whom I talked to, no one had an issue with her work as a prosecutor. A lot of them seemed to believe that only people doing dirt had issues with prosecutors. I thought of myself and my friends who have served long terms, knowing that in a way, Harris was talking about Black people’s needing protection from us — from the violence we perpetrated to earn those years in a series of cells.

Harris came up as a prosecutor in the 1990s, when both the political culture and popular culture were developing a story about crime and violence that made incarceration feel like a moral response. Back then, films by Black directors — “New Jack City,” “Menace II Society,” “Boyz n the Hood” — turned Black violence into a genre where murder and crack-dealing were as ever-present as Black fathers were absent. Those were the years when Representative Charlie Rangel, a Democrat, argued that “we should not allow people to distribute this poison without fear that they might be arrested” and “go to jail for the rest of their natural life.” Those were the years when President Clinton signed legislation that ended federal parole for people with three violent crime convictions and encouraged states to essentially eliminate parole; made it more difficult for defendants to challenge their convictions in court; and made it nearly impossible to challenge prison conditions.

Back then, it felt like I was just one of an entire generation of young Black men learning the logic of count time and lockdown. With me were Anthony Winn and Terell Kelly and a dozen others, all lost to prison during those years. Terell was sentenced to 33 years for murdering a man when he was 17 — a neighborhood beef turned deadly. Home from college for two weeks, a 19-year-old Anthony robbed four convenience stores — he’d been carrying a pistol during three. After he was sentenced by four judges, he had a total of 36 years.

Most of us came into those cells with trauma, having witnessed or experienced brutality before committing our own. Prison, a factory of violence and despair, introduced us to more of the same. And though there were organizations working to get rid of the death penalty, end mandatory minimums, bring back parole and even abolish prisons, there were few ways for us to know that they existed. We suffered. And we felt alone. Because of this, sometimes I reduce my friends’ stories to the cruelty of doing time. I forget that Terell and I walked prison yards as teenagers, discussing Malcolm X and searching for mentors in the men around us. I forget that Anthony and I talked about the poetry of Sonia Sanchez the way others praised DMX. He taught me the meaning of the word “patina” and introduced me to the music of Bill Withers. There were Luke and Fats; and Juvie, who could give you the sharpest edge-up in America with just a razor and comb.

When I left prison in 2005, they all had decades left. Then I went to law school and believed I owed it to them to work on their cases and help them get out. I’ve persuaded lawyers to represent friends pro bono. Put together parole packets — basically job applications for freedom: letters of recommendation and support from family and friends; copies of certificates attesting to vocational training; the record of college credits. We always return to the crimes to provide explanation and context. We argue that today each one little resembles the teenager who pulled a gun. And I write a letter — which is less from a lawyer and more from a man remembering what it means to want to go home to his mother. I write, struggling to condense decades of life in prison into a 10-page case for freedom. Then I find my way to the parole board’s office in Richmond, Va., and try to persuade the members to let my friends see a sunrise for the first time.

Juvie and Luke have made parole; Fats, represented by the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law, was granted a conditional pardon by Virginia’s governor, Ralph Northam. All three are home now, released just as a pandemic would come to threaten the lives of so many others still inside. Now free, they’ve sent me text messages with videos of themselves hugging their mothers for the first time in decades, casting fishing lines from boats drifting along rivers they didn’t expect to see again, enjoying a cold beer that isn’t contraband.

In February, after 25 years, Virginia passed a bill making people incarcerated for at least 20 years for crimes they committed before their 18th birthdays eligible for parole. Men who imagined they would die in prison now may see daylight. Terell will be eligible. These years later, he’s the mentor we searched for, helping to organize, from the inside, community events for children, and he’s spoken publicly about learning to view his crimes through the eyes of his victim’s family. My man Anthony was 19 when he committed his crime. In the last few years, he’s organized poetry readings, book clubs and fatherhood classes. When Gregory Fairchild, a professor at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia, began an entrepreneurship program at Dillwyn Correctional Center, Anthony was among the graduates, earning all three of the certificates that it offered. He worked to have me invited as the commencement speaker, and what I remember most is watching him share a meal with his parents for the first time since his arrest. But he must pray that the governor grants him a conditional pardon, as he did for Fats.

I tell myself that my friends are unique, that I wouldn’t fight so hard for just anybody. But maybe there is little particularly distinct about any of us — beyond that we’d served enough time in prison. There was a skinny light-skinned 15-year-old kid who came into prison during the years that we were there. The rumor was that he’d broken into the house of an older woman and sexually assaulted her. We all knew he had three life sentences. Someone stole his shoes. People threatened him. He’d had to break a man’s jaw with a lock in a sock to prove he’d fight if pushed. As a teenager, he was experiencing the worst of prison. And I know that had he been my cellmate, had I known him the way I know my friends, if he reached out to me today, I’d probably be arguing that he should be free.

But I know that on the other end of our prison sentences was always someone weeping. During the middle of Harris’s presidential campaign, a friend referred me to a woman with a story about Senator Harris that she felt I needed to hear. Years ago, this woman’s sister had been missing for days, and the police had done little. Happenstance gave this woman an audience with then-Attorney General Harris. A coordinated multicity search followed. The sister had been murdered; her body was found in a ravine. The woman told me that “Kamala understands the politics of victimization as well as anyone who has been in the system, which is that this kind of case — a 50-year-old Black woman gone missing or found dead — ordinarily does not get any resources put toward it.” They caught the man who murdered her sister, and he was sentenced to 131 years. I think about the man who assaulted my mother, a serial rapist, because his case makes me struggle with questions of violence and vengeance and justice. And I stop thinking about it. I am inconsistent. I want my friends out, but I know there is no one who can convince me that this man shouldn’t spend the rest of his life in prison.

My mother purchased her first single-family home just before I was released from prison. One version of this story is that she purchased the house so that I wouldn’t spend a single night more than necessary in the childhood home I walked away from in handcuffs. A truer account is that by leaving Suitland, my mother meant to burn the place from memory.

I imagined that I had singularly introduced my mother to the pain of the courts. I was wrong. The first time she missed work to attend court proceedings was to witness the prosecution of a kid the same age as I was when I robbed a man. He was probably from Suitland, and he’d attempted to rob my mother at gunpoint. The second time, my mother attended a series of court dates involving me, dressed in her best work clothes to remind the prosecutor and judge and those in the courtroom that the child facing a life sentence had a mother who loved him. The third time, my mother took off days from work to go to court alone and witness the trial of the man who raped her and two other women. A prosecutor’s subpoena forced her to testify, and her solace came from knowing that prison would prevent him from attacking others.

After my mother told me what had happened to her, we didn’t mention it to each other again for more than a decade. But then in 2018, she and I were interviewed on the podcast “Death, Sex & Money.” The host asked my mother about going to court for her son’s trial when he was facing life. “I was raped by gunpoint,” my mother said. “It happened just before he was sentenced. So when I was going to court for Dwayne, I was also going for a court trial for myself.” I hadn’t forgotten what happened, but having my mother say it aloud to a stranger made it far more devastating.

On the last day of the trial of the man who raped her, my mother told me, the judge accepted his guilty plea. She remembers only that he didn’t get enough time. She says her nose began to bleed. When I asked her what she would have wanted to happen to her attacker, she replied, “That I’d taken the deputy’s gun and shot him.”

Harris has studied crime-scene and autopsy photos of the dead. She has confronted men in court who have sexually assaulted their children, sexually assaulted the elderly, scalped their lovers. In her 2009 book, “Smart on Crime,” Harris praised the work of Sunny Schwartz — creator of the Resolve to Stop the Violence Project, the first restorative-justice program in the country to offer services to offenders and victims, which began at a jail in San Francisco. It aims to help inmates who have committed violent crimes by giving them tools to de-escalate confrontations. Harris wrote a bill with a state senator to ensure that children who witness violence can receive mental health treatment. And she argued that safety is a civil right, and that a 60-year sentence for a series of restaurant armed robberies, where some victims were bound or locked in freezers, “should tell anyone considering viciously preying on citizens and businesses that they will be caught, convicted and sent to prison — for a very long time.”

Politicians and the public acknowledge mass incarceration is a problem, but the lengthy prison sentences of men and women incarcerated during the 1990s have largely not been revisited. While the evidence of any prosecutor doing work on this front is slim, as a politician arguing for basic systemic reforms, Harris has noted the need to “unravel the decades-long effort to make sentencing guidelines excessively harsh, to the point of being inhumane”; criticized the bail system; and called for an end to private prisons and criticized the companies that charge absurd rates for phone calls and electronic-monitoring services.

In June, months into the Covid-19 pandemic, and before she was tapped as the vice-presidential nominee, I had the opportunity to interview Harris by phone. A police officer’s knee on the neck of George Floyd, choking the life out of him as he called for help, had been captured on video. Each night, thousands around the world protested. During our conversation, Harris told me that as the only Black woman in the United States Senate “in the midst of the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery,” countless people had asked for stories about her experiences with racism. Harris said that she was not about to start telling them “about my world for a number of reasons, including you should know about the issue that affects this country as part of the greatest stain on this country.” Exhausted, she no longer answered the questions. I imagined she believes, as Toni Morrison once said, that “the very serious function of racism” is “distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.”

But these days, even in the conversations that I hear my children having, race suffuses so much. I tell Harris that my 12-year-old son, Micah, told his classmates and teachers: “As you all know, my dad went to jail. Shouldn’t the police who killed Floyd go to jail?” My son wanted to know why prison seemed to be reserved for Black people and wondered whose violence demanded a prison cell.

“In the criminal-justice system,” Harris replied, “the irony, and, frankly, the hypocrisy is that whenever we use the words ‘accountability’ and ‘consequence,’ it’s always about the individual who was arrested.” Again, she began to make a case that would be familiar to any progressive about the need to make the system accountable. And while I found myself agreeing, I began to fear that the point was just to find ways to treat officers in the same brutal way that we treat everyone else. I thought about the men I’d represented in parole hearings — and the friends I’d be representing soon. And wondered out loud to Harris: How do we get to their freedom?

“We need to reimagine what public safety looks like,” the senator told me, noting that she would talk about a public health model. “Are we looking at the fact that if you focus on issues like education and preventive things, then you don’t have a system that’s reactive?” The list of those things becomes long: affordable housing, job-skills development, education funding, homeownership. She remembered how during the early 2000s, when she was the San Francisco district attorney and started Back on Track (a re-entry program that sought to reduce future incarceration by building the skills of the men facing drug charges), many people were critical. “ ‘You’re a D.A. You’re supposed to be putting people in jail, not letting them out,’” she said people told her.

It always returns to this for me — who should be in prison, and for how long? I know that American prisons do little to address violence. If anything, they exacerbate it. If my friends walk out of prison changed from the boys who walked in, it will be because they’ve fought with the system — with themselves and sometimes with the men around them — to be different. Most violent crimes go unsolved, and the pain they cause is nearly always unresolved. And those who are convicted — many, maybe all — do far too much time in prison.

And yet, I imagine what I would do if the Maryland Parole Commission contacted my mother, informing her that the man who assaulted her is eligible for parole. I’m certain I’d write a letter explaining how one morning my mother didn’t go to work because she was in a hospital; tell the board that the memory of a gun pointed at her head has never left; explain how when I came home, my mother told me the story. Some violence changes everything.

The thing that makes you suited for a conversation in America might be the very thing that precludes you from having it. Terell, Anthony, Fats, Luke and Juvie have taught me that the best indicator of whether I believe they should be free is our friendship. Learning that a Black man in the city I called home raped my mother taught me that the pain and anger for a family member can be unfathomable. It makes me wonder if parole agencies should contact me at all — if they should ever contact victims and their families.

Perhaps if Harris becomes the vice president we can have a national conversation about our contradictory impulses around crime and punishment. For three decades, as a line prosecutor, a district attorney, an attorney general and now a senator, her work has allowed her to witness many of them. Prosecutors make a convenient target. But if the system is broken, it is because our flaws more than our virtues animate it. Confronting why so many of us believe prisons must exist may force us to admit that we have no adequate response to some violence. Still, I hope that Harris reminds the country that simply acknowledging the problem of mass incarceration does not address it — any more than keeping my friends in prison is a solution to the violence and trauma that landed them there.

In light of Harris being endorsed by Biden and highly likely to be the Democratic Party candidate, I thought I would share this balanced, understanding of both sides, article in regard to Harris and her career as a prosecutor, as I know that will be something dragged out by bad actors and useful idiots (you have a bunch of people stating 'Kamala is a cop', which is completely false, and also factless and misleading statements about 'mass incarceration' under her). I'm not saying she doesn't deserve to be criticised or that there is nothing about her career that can be criticised, but it should at least be representative of the truth and understanding of the complexities of the legal system.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

“'We chose to file this case on May 1, in solidarity with workers around the world, because ending forced prison labor in ADOC isn’t just about stopping the State’s extractive profiteering from the labor of Black people – both inside and outside of prisons. It’s also about eliminating the control that forced prison labor enables the State to exercise over Black people – an extension of the control exerted by the State through slavery, the Black Codes, convict leasing, and Jim Crow,' said CJ Sandley, Staff Attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represents the workers through its Southern Regional Office.

The six plaintiffs – Trayveka Stanley, Reginald Burrell, Dexter Avery, Charlie Gray, Melvin Pringle, and Ranquel Smith – have all been punished or threatened with punishment for resisting forced work. ... 'I am motivated by my passion to fight for an end to all injustice. That passion burns brighter than my fears. We must stand for something or we will fall for anything. This lawsuit is about the unpaid, overbearing state jobs that I, as well as my fellow inmates, are being forced to work against our will. According to Article I, Section 32, this is against the law,' says Plaintiff Trayveka Stanley, currently incarcerated at Montgomery Women’s Facility in Montgomery, Alabama.

According to Plaintiff Reginald Burrell, who is incarcerated at Decatur Work Release in Decatur, Alabama: 'The most influential public officials in the State of Alabama today remain loyal to and act in unity with their racist slave legacy from the Confederacy and the Jim Crow era, continuing to deliberately make, enforce, and defend bad policy decisions and practices, knowing it results in the demise, disadvantages, and disenfranchisement of poor whites and African-Americans, perpetuating hopelessness, despair, and excessive suffering in our lives today, and knowing it induces, in many circumstances, desperate choices under duress, to give themselves reason to enslave us through incarceration by the Alabama Department of Corrections for the sole purpose of continuing forced labor, slavery, and involuntary servitude in this state.'”

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Atlanta to Chicago [...]. These cop cities are training grounds for police violence and must be dismantled to restore a world where life is precious.

In a stunning yet utterly predictable act, Chicago’s “cop academy” has officially opened on the West Side complete with a ribbon-cutting in front of fake street signs and fake housing.

In a city reeling from extreme poverty, a lack of affordable housing, myriad environmental injustices, food apartheid, [...] and in a city where at least 65,000 people are experiencing homelessness, the leadership of the city of Chicago spent $128 million to build fake homes on the city’s resource-starved West Side where officers can practice the violence and brutality that they will mete out to Chicago residents.

---

In a disturbing photo, Mayor Lightfoot, [...] Fire Commissioner Nance-Holt and others smile while cutting a red ribbon, proud to have brought this into being. Adding insult to injury, the thirty-two-acre cop academy was built on the city’s West Side, where decades of racist policy (such as redlining and other housing discrimination and disinvestment) by the city government in this majority-nonwhite community have already given way to poverty and population loss. (In just one example, the Rahm Emanuel administration closed half of the West Side’s mental health clinics in 2012, then shuttered numerous West Side schools in his historic closure of fifty schools in 2013.) [...]

---

Lest there be any doubt as to whether or not West Siders actually want this cop academy, in 2018 the organizers of the No Cop Academy campaign polled West Garfield Park residents [...]. 95 percent recommended that the city invest in something else - beyond the Chicago Police Department [...]

What kind of society eagerly spends millions of dollars to build fake neighborhoods, but cannot muster the funds to provide actual housing for the unhoused? What kind of society would rather stage and practice violence than provide mental health resources or violence interruption to communities reeling from it everyday? Unfortunately, such questions arise on a routine basis in this city.

---

And it is not only in this city. [...] For Chicago, like so many cities across the US, we must remember that policing is not a “rational” response to something called “crime.” Instead, it is a war on poor people (particularly Black and Brown poor people). As Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, this war treats incarceration as a solution to social and economic ills while conveniently stripping poor and working-class people of color of their political rights and autonomy. [...]

---

Additionally, in a cynical move decried by Chicago youth organizers, a chapter of the Boys and Girls Club is set to open at the facility. This is despite Chicago having the second most killings by police of youth under eighteen in the country, and despite several high-profile CPD murders of youth such as thirteen-year-old Adam Toledo and twenty-two-year-old Anthony Alvarez just in the last few years. [...]

They want a fake village where no one lives or thrives. They spend millions on a theme park to practice surveilling, policing, and controlling people. This vision can never be a home for anyone, and thus the Cop Academy should have no place in our city if we are to make Chicago, someday, a true home for its residents. [...]

--

We must refuse to allow such sadism to become normalized, and continue to make clear in the face of a city leadership which laughs, that, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, “where life is precious, life is precious.” [...]

Like the brave protesters facing off against the horrific violence of Atlanta’s proposed Cop City, organizers in Chicago have fought a valiant campaign against the cop academy since it was first proposed during the Emanuel administration. The No Cop Academy campaign, led by Black youth across the city, has led countless protests and actions and was endorsed by more than 100 organizations. [...]

Though the structures have been built, the fight against the cop academy (as well as similar projects in Atlanta and elsewhere) must continue: we must transform every fake cop neighborhood into real, affordable housing and vibrant neighborhoods where every person has what they need to thrive.

---

Text by: Nisha Atalie. “From Atlanta to Chicago, Cop Cities Breed Violence.” Rampant Magazine. 30 January 2023. [Italicized first paragraph in this post is directly quoted from the title and subheading printed alongside the article at Rampant.]

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“The history of the transatlantic slave trade and chattel slavery looms large in contemporary trafficking conversations – often in the form of claims, subtle or not, that modern trafficking is worse than chattel slavery. Politicians and police officers meet to tell each other that ‘there are more slaves now than at any previous point in human history’; a UK former government minister insists that ‘we are facing a new slave trade, whose victims are tortured, terrified East European girls rather than Africans’. Matteo Renzi, then prime minister of Italy, wrote in 2015 that ‘human traffickers are the slave traders of the twenty-first century’. The Vatican claimed that ‘modern slavery’, specifically prostitution, is ‘worse than the slavery of those … who were taken from Africa’. A senior British police officer remarked that ‘the cotton plantations and sugar plantations of the eighteenth and nineteenth century … wouldn’t be as bad as what some victims [today] go through’.

A 2012 anti-trafficking ‘documentary’ that was screened for politicians and policymakers around the world, including in Washington, London, Edinburgh, and at the UN buildings in New York, proclaims: ‘In 1809 the cost of a slave was thirty thousand dollars. In 2009, the cost of a slave is ninety dollars.’ White people co-opting the history of chattel slavery as rhetoric is grim, not least because the term slavery names a specific legal institution created, enforced and protected by the state, which is nowhere near synonymous with contemporary ideas of trafficking. Indeed, the direct modern descendant of chattel slavery in the US is not prostitution but the prison system. Slavery was not abolished but explicitly retained in the US Constitution as punishment for crime in the Thirteenth Amendment of the Bill of Rights, which states that ‘neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction’ (emphasis ours).

The Thirteenth Amendment isn’t just a vestigial hangover. In 2016, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee released a statement condemning inmates’ treatment in the prison work system:

Overseers watch over our every move, and if we do not perform our appointed tasks to their liking, we are punished. They may have replaced the whip with pepper spray, but many of the other torments remain: isolation, restraint positions, stripping off our clothes and investigating our bodies as though we are animals.

There are more Black men in the US prison system now than were enslaved in 1850. Seeking to ‘end slavery’ through increased policing and incarceration is a bitterly ironic proposition.

White people in Britain and North America have been very successful at ducking any real reckoning with the legacies of the slave trade. Historian Nick Draper writes, ‘We privilege abolition … If you say to somebody ‘tell me about Britain and slavery’, the instinctive response of most people is Wilberforce and abolition. Those 200 years of slavery beforehand have been elided – we just haven’t wanted to think about it.’ By rhetorically intertwining modern trafficking with chattel slavery, governments and campaigners have been able to hide punitive policies targeting irregular migration behind seemingly uncomplicated righteous outrage.

Men of colour become ‘modern enslavers’ who deserve prosecution or worse. Their ‘human cargo’, figured as being transported against their will, are owed nothing more than ‘humanitarian return’, and the racist trope of border invasion is given a progressive sheen through collective shared horror at the villainy of the perpetrators. Meanwhile, in crackdowns and deportations, European governments position themselves as re-enacting and re-writing the history of anti-slavery movements to make themselves both victims and heroes. Of course, these actions by European governments do harm. For example, their policy of confiscating or destroying smuggling boats has not ‘rescued’ anyone, only induced smugglers to send migrants in less valuable – and less seaworthy – boats, leading to many more deaths. This policy continued for years, despite clear evidence that it was causing deaths. But, faced with twenty-first century ‘enslavers’, there is little need for white reflection. Instead, Renzi later wrote that European nations ‘need to free ourselves from a sense of guilt’ and reject any notion of a ‘moral duty’ to welcome arrivals. At the time of writing, the Italian government’s ‘solution’ to the migrant crisis is to pay for migrants to be incarcerated, stranded in dangerous, disease-ridden detention centres in Libya. As Robyn Maynard writes,

By hijacking the terminology of slavery, even widely referring to themselves as ‘abolitionists’, anti–sex work campaigners … in pushing for criminalization … are often undermining those most harmed by the legacy of slavery. As Black persons across the Americas are literally fighting for our lives, it is urgent to examine the actions and goals of any mostly white and conservative movement who [claim] to be the rightful inheritors of an ‘anti-slavery’ mission which aims to abolish prostitution but both ignores and indirectly facilitates brutalities waged against Black communities.

What does the fight to save people from ‘modern slavery’ look like on the ground? In 2017, police in North Yorkshire told journalists that they were fighting to rescue ‘sex slaves’ and asked members of the public to call in with tips, adding that the ‘sex slaves’ themselves ‘are prepared to do it [sell sex], they believe there is nothing wrong in it … We have just got to … educate them that they are victims of human trafficking.’ It seems fairly obvious that women who are ‘prepared to do it’ and ‘believe there is nothing wrong with it’ will not particularly benefit from being ‘educated’ about the fact that they are victims of trafficking – which in England and Wales means a forty-five-day ‘respite period’ (frequently disregarded) followed by a ‘humanitarian’ deportation.”]

molly smith, juno mac, from revolting prostitutes: the fight for sex workers’ rights, 2018

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Americans: Vote Locally. Do it.

There seems to be a common misconception that the presidential election is the most important one not just for the USA, but for the world - WRONG!

Let me be clear: You should vote in the Presidential election.

Historically, young people don't vote. Even though young voter turnout has increased drastically since Trump, local voting is still largely being determined by conservative older generations.

Importantly, you should be voting locally in part because this is the largest influence over who gets nominated in the Primary and how your opinion is vocalized on a national scale. Also:

voter restriction/suppression

climate change efforts/issues (such as pipelines getting built)

policing, law enforcement and mass incarceration

availability of affordable housing, public transport, disability relief

education - as in, whether or not PragerU gets taught in schools

If you are worried about "being selfish" for focusing smaller local issues instead of global ones (such as the current genocide), I understand. However, this is a more effective way to pressure the current President - local legislators have more voice than we do. This is also setting up a less racist, genocidal future for global politics because Presidential nominees are almost always picked from State level positions.

The Presidential election helps people to feel good/bad about an "immediate" measurable result from a single action. But the truth is that the Bidens of the US will keep being the only rival to "I want to be a dictator" Trumps if we don't start investing our votes from the ground up.

Here is a guide (mostly from this website https://tminstituteldf.org/local-elections/ ):

CITY GOVERNMENT

School Boards:

Have the power to set policy and budgets for local schools, such as whether or not you can protest without losing your job or getting expelled.

Sherrifs:

Generally speaking, Sherrifs are fucked up. It's too much for me to go into here. They have way too much unilateral power with no oversight at all.

youtube

Prosecutors:

The largest contributor to mass incarceration

They set the terms on whether someone is charged with a misdemeanor or felony and being convicted of a felony will strip your right to vote in many states - some permanently.

City Council:

City Council approve things like city budgets and implement criminal and civil laws and regulations

Also the voice of their City at a State and Federal level. Generally, these are some of the people you should be shouting at to bring your voice higher up the food chain.

This includes the Mayor who often decides where budgets go (like schools or cops), and they also determine the level of enforcement of local laws.

County Board of Supervisors (County Commissioners):

Represent county issues in front of state and federal legislative bodies. Counties are also responsible for registering voters and administrating elections. i.e., another group of people who have a stronger voice against the elected Democrat when it comes to larger issues.

Planning and Zoning Commission:

Determines how and where affordable housing is zoned in your area. Has a huge effect on housing segregation.

Comptroller:

The City's accountant and budget manager - this is the person who audits the City Council and makes sure they aren't basically stealing money. They also approve city contracts such as those for affordable public transportation and shelters.

STATE GOVERNMENT

Judges:

This one is crucial. Your state judges act as the Supreme Court of your given state. The cases that they weigh on when it comes to state laws (such as abortion, medical autonomy, immigration, right to protest/free speech, etc.) these are binding and final.

Superintendent of Education:

This is the person who decides if PragerU gets to teach classes on why Zionism and Evangelical teachings are "ok and good, actually".

Secretary of State:

The person who certifies elections in your state - for the Presidency, but also for all of these other positions mentioned. It is so, so important that this person cannot be bought or pressured.

Attorney General:

Has influence over law enforcement agencies and represents the state in legal disputes - such as those where someone is disputing their rights are being infringed by the state. (abortion, medical autonomy, immigration, right to protest/free speech, etc.)

Governor:

Is basically the president of your state. They sign in laws, have veto power and oversee all of the other departments. They also can appoint Justices and State Senate seats if they are empty.

Not only does this person have a lot of state power, they also have a ton of influence over the broader federal climate and are one of the positions that fast-tracks to Presidency (see: Ron Desantis).

State Comptroller (or Controller):

Same as City Comptroller except extremely importantly they manage disaster relief/preparation funding - which is especially important amidst climate change.

Also oversee fraud investigations.

Public Service Commissioner:

Determines rates for things like energy, water, internet in your state.

Also deals with the gas and oil industry in your state, often being in charge of approval/rejection of the building of oil pipelines.

They can be appointed by the Governor.

State Senators:

Has just about the most authority in a state, with the ability to impeach Governors and deny someone the Governor tries to appoint

Another position that fast-tracks to Presidency

Draft and introduce/pass state laws and amend the state constitution

State House of Reps:

Can call for the removal of another legislator

Draft and introduce/pass state laws

All Right. I'm running out of steam on this post. Please, please, please, PLEASE register to vote *right now* and look over the website when you do to see if it can set up email alerts when an election is coming up.

Buy a calendar and mark voting days and stick it to your wall TODAY. Set aside an hour of your time, TODAY, to make a plan for voting.

Go to this website, enter your state. It will tell you exactly what to do. Register.

Lastly, if you don't like Biden and it makes you feel like shit to vote for him (understandably), then YOU NEED TO VOTE IN THE PRIMARY.

#us politics#politics#voting#us voting#I am sure I missed some shit here but I am tired and I don't usually make long posts like this#this took HOURS ok#listen I get it if you don't like biden I really truly do he is complicit in a genocide I GET IT#but if you think that trump winning is going to send some kind of message buddy you're just plain wrong#I am not saying vote blue cause I think democrats are good or because I'm a floppy liberal or whatever#you can do more than one thing at a time and imo voting blue for president is the bare minimum WHILE you protest & do public outreach#long post#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://youtu.be/7oFu2pNnRIc

Where did you think Top Cop Harris come from

Hey, I'm not the most knowledgeable on this subject, but yes, I have heard that Kamala called herself Top Cop while she was District Attorney.

The only two posts on my blog that address this have imo pretty nuanced takes on this, which boil down to:

Kamala is not perfect, but we can't wait for a perfect candidate to magically appear

Therefore, you can absolutely criticize her for things she did, things she contributed to, things that happened on her watch

But you should criticize her for what really happened. People may not know that she wasn't a uniformed officer who physically arrested people. She got into law to protect women and children from abuse

Yes, she was upholding a corrupt and racist system. But criticize her for that. Not for lies

We can talk about the nuances of what she WAS, but we first have to correct the mistaken impression of what she WASNT

.

Additionally, I think it should be allowed to feel hope for a candidate that isn't as bad as you thought. It's allowed to correct some misinformation around you

I'm not looking at this election like she's some savior who will fix the world just bc she's not really a cop. I'm hoping that ppl won't write her off based on inaccurate information, only accurate information. Bc the only other alternative is That Guy

.

Again, I'm not an expert on this. But the takes that I elevate aren't only the ones that I like or agree with; they're the takes that I think make a good point or are worth chewing on.

Some greatest hits from this post:

Be careful what you read, always be critical of how facts are presented to you, and don't be afraid to admit when you're wrong.

There's no such thing as a good cop, but there do exist naive cops with good intentions who think they can change the system from within

The real nuance is that the position of "top cop" or whatever can't be left empty. When you're filling out the ballot and get to sheriffs and prosecutors, every candidate is an acab. There are no right choices simply by what the nature of the job is. But there are candidates who will attempt that incremental change, and ones who can make things much worse.

She gets my vote at least, she's definitely better than trump or biden, but I'm still hesitant to give my absolute full support.

And from this post:

It didn’t hit me until recently that people genuinely think Kamala Harris was a police officer because of all the people who call her a cop online.

We can discuss how related that is to police work and how tied she is to the carceral system etc etc (but for fairness would have to include her record of pushing for lowering incarceration rates through programs helping former prisoners + her office refusing to jail folks for low level weed offense). But she was never a police officer.

I think it’s important to note she learned and grew over time, as well.

What drives me crazy about the prosecutor/district attorney = cop common line of leftist thinking is that. People always talk about when a progressive DA is appointed, and how important that is, because the DA literally can just decide not to prosecute certain offenses.

I’d also like to add that if you look at her record in a timeline she has gotten progressively more liberal!

#some ppl will call it pandering but uhhhh we literally want our politicians to listen to our concerns and change their policies based on it

We vote for the weakest adversary. The weakest adversary is always the politician who mostly agrees with you but got where they are by compromising with an unjust system. Elect that person and mush their face in the compromises they’ve made and we can undo the fucked up laws and practices !!!! Or you can let someone who can never be convinced because they hold opposite views on criminalization, incarceration, police brutality and immunity, etc. If you don’t understand or care that voting works this way, where’s your pipe bombs and guerilla fighter cells? Cause that or complacency with fascist takeover is all you’re eating

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.

#youre not gonna budge trump #but if youre not happy with kamala #nudge her left! #dont let perfect be the enemy of good #or progress #we're still on the wrong side of the line #but how are we going to get to the right side without taking a single step?

#asks#anon#us politics#kamala harris#top cop#i speak#i link#i quote#i ramble in the tags#not even a hello#lol#acab#obviously#the nuanced posts talk about that#but i figured that wasnt the issue for you#i try to be discretionary in the takes that i elevate#obviously i mostly copy or rb takes that i agree with#but sometimes i rb something just bc i wanna chew on it#i want to preserve that perspective so i can find it again later#same with comments i copy#i dont look at everything on my blog as#i cosign this#i think of my blog as a collection of interesting thoughts and takes that ppl have shared with me#one of the posts explicitly talks about#be critical of how facts are presented to you#yes she called herself top cop#she still wasnt a cop#first impressions matter#we can talk about the nuances of what she WAS#but we first have to correct the mistaken impression of what she WASNT

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

No one lends ʌ hand towards black Americans but everyone needs ʌ lending hand from us.

No one deserves death and loss. But this is life. War will hæsapupenun take it up with the banks because they control it.

My life does not depend on backing anyone but my people.

How dare you ask for the prayers from people you condemned before the war.

♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️♠️

Many are unaware of the racist policies in Israel. Jews are forbidden to rent to Black people, as a result Blacks are segregated. Jews also mistreat Blacks in their Synagogues of Satan, and this treatment stems from a deeply seated belief that Blacks are inferior monkeys. The following was written by their infamous Maimonides, the man who "collectively" put together the Talmud and its "ORAL LAWS" of hell. Those who are incapable of attaining to supreme religious values include the black colored people and those who resemble them in their climates. Their nature is like the mute animals. Their level among existing things is below that of a man and above that of a monkey.”

On March 17, one of Israel’s two chief rabbis, Yitzhak Yosef, called black people “monkeys” and the Hebrew equivalent of the N-word in his weekly sermon.

It is highly unlikely that Yosef will face any real repercussions for his racist comments.

The Israeli Arabs are where African Americans were in the 1960s. They are a somewhat marginalized minority in Israeli society. They are behind the Jews in income, education, and infrastructure/government services but have been steadily improving their condition and status for decades.

Unfortunately, their political leadership has served them poorly.

incarcerated at a rate that is 760% higher than their proportion in Israeli society.2

Forty percent of soldiers of Ethiopian origin have been imprisoned.2

Mizrahi Israelis receive 20% less income than their Ashkenazi counterparts.3

Mizrahi Israelis have on average 18% lower education attainment compared to Ashkenazi Israelis.

#hoodoo#medium#witch#ancestor veneration#rootwork#black women#conjure#prophet#tutnese#luxury#FBA#Tariq nasheed#foundational black american#isreal

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey, gonna doxx myself for a cause here:

Washington, DC's government voted on February 6th to advance restrictive and dangerous legislation that they claim will increase the safety of District residents (article updated 2/5/23). This bill allows police to harass and arrest people for such offenses as gathering in groups of more than two people, wearing a mask, or not immediately offering up your name and address if asked by a transit cop. DC's racist police force is bound to use these policies to incarcerate yet more Black DC residents.

There is a second vote on March 5th. Other DC people, I'd encourage you to look into the bill and read this letter to the DC council. There is also a link in the letter to add your signature. Talk to your fellow DC residents! Speak out! Protect our community from the threat of increased police surveillance and violence!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'UK Warmly Embraces Russia's Benevolent EU Policy' #DeepAIGeneratedImage #PoliticalSatire Fishy Rishi Artworks Llewelyn Pritchard 18 February 2024

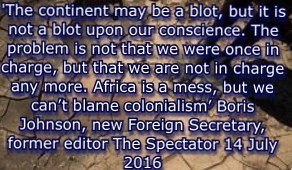

https://lnkd.in/eQZqzSDM https://lnkd.in/evZPUDAm Johnson's unsuitability to be Foreign Secretary and PM was demonstrated for example, by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s imprisonment by the Iranian government and by his shameful white supremacist, patriarchal, racist, colonial stated views about indigenous peoples in Africa:

'Why was Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe arrested? A timeline of her detention and sentence in Iran. British-Iranian national spent six years incarcerated in Tehran following her arrest in 2016'

EXTRACT

'6 November 2017: It is feared Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe may face a further period of imprisonment because of remarks made by then-foreign secretary Boris Johnson. Mr Johnson told a parliamentary committee the previous week that Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe was working in Tehran training journalists at the time of her arrest in 2016.

Four days later, she was summoned before an unscheduled court hearing, where the foreign secretary’s comments were cited as proof that she was engaged in “propaganda against the regime”.

7 November 2017: It is announced that Mr Johnson told his Iranian counterpart in a phone call that his comments to a Commons committee provide “no justifiable basis” for further legal action against Ms Zaghari-Ratcliffe. A Foreign Office spokesman says Mr Johnson accepted he ���could have been clearer”' Read more

https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vSt098wd0KJAMM6-mwGSnHvUoVPcipmbpWEZksdKdSxY_YGuGB5s3t5DPkVwPcfEdqZlB_ydd6gKqWl/pub ‘The continent may be a blot, but it is not a blot upon our conscience. The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more.’ ‘Africa is a mess, but we can’t blame colonialism’ Boris Johnson, new Foreign Secretary and former editor of the magazine. The Spectator 14 July 2016

youtube

https://theguardian.com/politics/2017/sep/30/boris-johnson-caught-on-camera-reciting-kipling-in-myanmar-temple Boris Johnson, Foreign Secretary’s impromptu recital of colonial-era poem was so embarrassing the UK Ambassador was forced to stop him. Robert Booth 30 September 2017 #Corruption #CorruptToryGovernment #CorruptColonialLawUKCA

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/treating-traditional-patriarchal-mismanagement-tory-pritchard-ma-laime/ https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vQ3f8j7NZEVYH-yADTY60BnzO76CoRMO5Ktc3OQDcoL4N-TpxIaceDLPeXlGFh_STnBwzvK_L2c6LZU/pub Treating traditional, patriarchal, colonial misMANagement by corrupt Tory government UK ‘just as a nightmare’ particularly Rishi Sunak (PM no nationally elected mandate) and Boris Johnson ‘Traitor UK' is unhelpful for several reasons ... Scroll Right Down to find out more #AI #Perplexity Llewelyn Pritchard 17 January 2024

#humanrights#climatejustice#uk#corruption#ai#education#climatecrisis#peopledie#rightsofnature#Corruption#VladimirPutin#TheKremlin#CorruptKremlin#Liars#HouseOnFire#Lying#SerialLiars#BorisJohnson#RishiSunak#COVIDJustice#BrexitJustice#HumanRights#ClimateJustice#SocialJustice#ClimateJusticeIsSocialJustice#ActNow#TellTheTruth#BeTheChange#ClimateCriminals#JailTime

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Rav Arora

Published: Dec 22, 2020

We are frequently told by commentators and theorists on the progressive and liberal Left that we live in a systemically racist and patriarchal society. The belief that Western societies privilege white men and oppress people of color, women, and LGBT citizens is especially popular within academic institutions, legacy media, the entertainment industry, and even sports. However, newly released statistics from the US Department of Labor for the third quarter of 2020 undermine this narrative. Asian women have now surpassed white men in weekly earnings. That trend has been consistent throughout this past year—an unprecedented outcome. Full-time working Asian women earned $1,224 in median weekly earnings in the third quarter of this year compared to $1,122 earned by their white male counterparts. Furthermore, the income gap between both black and Latino men and Asian women is wider than it has ever been. The income gap between white and black women, meanwhile, is much narrower than the gap between their male counterparts.

These outcomes cannot exist in a society suffused with misogyny and racism. As confounding to conventional progressive wisdom as these new figures appear to be, copious research finds that ethnic minorities and women frequently eclipse their white and male counterparts, even when these identities intersect. Several ethnic minority groups consistently out-perform whites in a variety of categories—higher test scores, lower incarceration rates, and longer life expectancies. According to the latest data from the US Census Bureau, over the 12 months covered by the survey, the median household incomes of Syrian Americans ($74,047), Korean Americans ($76,674), Indonesian Americans ($93,501), Taiwanese Americans ($102,405), and Filipino Americans ($100,273) are all significantly higher than that of whites ($69,823). The report also finds substantial economic gains among minority groups. Valerie Wilson at the Economic Policy Institute reports that from 2018 to 2019, Asian and black households had the highest rate of median income growth (10.6 percent and 8.5 percent, respectively) of all main racial groups (although she cautions that overall disparities remain “largely unchanged”). On a longitudinal scale, Hispanics, not whites, had the highest income growth in 2019 relative to the start of the Great Recession in 2007 (although many of these gains have been reversed by the pandemic).

Rapidly rising female economic success is partly a product of higher academic representation. 2019 was the 11th consecutive year in which women earned the majority of doctoral degrees. Women accounted for 57 percent of all students across American colleges in 2018 according to the latest US Department of Education figures and earned the majority of associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees. According to University of Michigan economist Mark J. Perry, “By overall enrollment in higher education men have been an under-represented minority for the last 40 years.” Sex differences in cognition can help to explain differential performance along gender lines—although men typically perform better on quantitative and visuospatial tasks, several studies have found that on average women perform better in verbal and memory tasks and on reading and writing tests. According to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development:

At the primary level, boys and girls do equally well in mathematics and science but girls have a clear advantage in reading (OECD, 2012a). At the secondary level while girls maintain their advantage in reading a gap in favour of boys emerges in mathematics… [T]he gender gap in reading is much larger than the gap in mathematics. On average, the reading gap was equal to 38 points in PISA 2012, which roughly equals one year of schooling. The gap in mathematics was nine points on average.

These disparities can be explained by several factors. Studies have found that girls are more self-disciplined and better at listening, whereas boys tend to be more rebellious, more aggressive and, contrary to popular wisdom, more socially exclusionary in school. Research has also found that girls mature in certain cognitive and emotional areas faster than boys, with girls’ brains developing up to two years earlier during puberty which can give them an academic performance advantage in school.

* * *

The specious concept of intersectionality underpins the oppression narratives advanced by contemporary progressive activists. Its advocates hold that class, race, sexual orientation, age, gender, and disability can compound an individual’s oppression or privilege. For example, an ethnic woman not only faces racism and sexism, but also a third intersecting prejudice (known as “misogynoir” in the case of black women) that ethnic men and white women do not experience. So, ethnic women are more oppressed and that oppression is central to their identity and delimits their success in our society.

Apart from the most obvious theoretical flaw of intersectionality—that it flattens the diverse complexity of human experience into a few arbitrary characteristics—its validity falls apart under empirical scrutiny. For example, despite the greater oppression black women supposedly face compared to white women, a much-publicized 2018 study featured in the New York Times found that black women had slightly higher incomes than white women raised in families with comparable earnings. The earnings of black men, on the other hand, were found to be consistently much lower than those of white men from similar economic backgrounds. Controlling for parental earnings, black women were found to have higher college attendance rates than white men.

A study from the University of Michigan compared the earnings trajectories of African immigrant women and men to their US-born counterparts. The (very left-leaning) researchers went into the study with an intersectional analytic framework, stating: “The double disadvantage would predict that black African women would be disadvantaged by the interaction of their race and gender.” But having analyzed the data, the authors concluded: “However, these are not the patterns that we found.” While African-born black men had lower earnings than US-born white men, African-born black women had higher earnings than US-born white women. Interestingly, the researchers found that the income growth rate of female African immigrants has outpaced that of both US-born men and women. Black female immigrants from Africa saw a 130 percent rise in their income between 1990 and 2010, eclipsing the earnings of both white and black American women. No variance of the oversimplified “institutionalized racism” or intersectionality framework can adequately explain these complex socioeconomic outcomes, even when the researchers are biased in that direction.

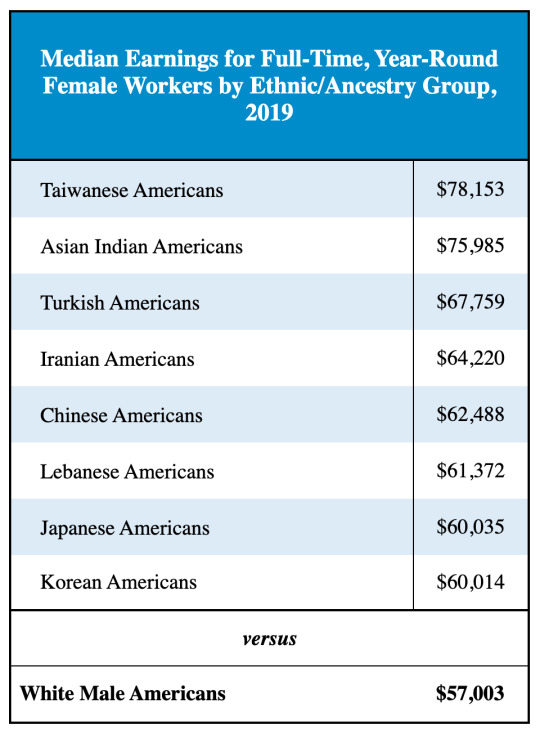

Intersectionality is such a misconceived lens through which to understand the world that often white men fare worse than some of the most “oppressed” victim groups in our society. For example, the latest Census data indicate that the median earnings for full-time, year-round female Palestinian American workers ($52,061), female Iranian American workers ($64,220), and female Turkish American workers ($67,759) were all higher than those of white women ($45,581). Turkish and Iranian women also out-earned white men ($57,003). The vast majority of these women have not two but three “oppression variables” because of their gender, ethnicity, and religion (Islam).

Perceived discrimination is necessarily subjective and a kind of minority bias can skew perception of racial bias. Nevertheless, I don’t doubt that many women of color face discrimination on account of their gender, ethnicity, or religion, or all three. According to a 2017 Pew survey, 83 percent of US Muslim women said there was a lot of discrimination against Muslims and more than half of US Muslim women said they had experienced anti-Muslim discrimination in the past 12 months at the time of the survey. However, if economic outcomes are to be taken seriously, the power of “intersecting” sexism, Islamophobia, and racism does not appear to be a barrier to success or sufficient to suppress human potential. To the contrary, intersectional theory broadly exaggerates the magnitude and impact of prejudice in our society, and gives the illusory impression of a zero-sum societal competition between groups. As Jordan Peterson has argued, intersectionality “devolve[s] people back into tribal antagonism.”

youtube

* * *

Asian success in the West has long been disputed as an example of the “model minority myth” that critics say is used to downplay the impact of societal racism. Asian immigrants, they argue, come from the highly educated upper echelons of their home countries, which gives them an advantage over native-born citizens. But this claim is self-refuting—it admits that “human capital” (familial values, vocational skills, work ethic, conducive cultural patterns) supersedes perceived discrimination and the impact of any systemic or institutional racism. Immigrants who arrive in a new land to which they are not acculturated, but whose intelligence and cultural habits allow them to outperform native whites over time, repudiate a progressive narrative that insists race and not merit determines success.

While immigration selectivity does factor into relative Asian success, it only accounts for part of the reason certain Asian groups have excelled in the West—immigrant groups are not uniformly educated or economically well-off. For example, about 50 percent of Chinese, Pakistani, Indonesian, Korean, and Filipino immigrants have a bachelor’s degree or higher. But the same is true of only a quarter of Vietnamese immigrants—fewer than white Americans (35 percent in 2016). Syrian immigrants have roughly the same level of education as white Americans, yet Syrian Americans and the rest of these aforementioned groups out-earn whites according to the latest data. This is despite the fact that language barriers disadvantage immigrants relative to native-born Americans. Only 34 percent of Vietnamese immigrants and 51 percent of Japanese immigrants (to take two examples) are proficient in English (compared with virtually all of white Americans), yet they still have higher household median incomes than whites by about $2,000 and $15,000, respectively. The idea that all—or most—immigrants are preconditioned for success is a myth. Selectivity is only one part of the puzzle.

Some immigrant groups with high rates of poverty defy the odds and flourish in the US. For example, the children of immigrants from Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos routinely attain high levels of academic achievement despite their low socioeconomic status compared to whites. In their paper, “Culture and Asian-White Achievement Difference,” University of Michigan sociologists Airan Liu and Yu Xie offer a meta-analysis of the available literature on Asian academic achievement. They find that:

Qualitative research indicates that even Asian American children from disadvantaged family backgrounds enjoy the Asian premium in academic achievement (e.g., Lee and Zhou, 2014), which suggests that access to more and better home resources is not the key to their success.

Several studies that control for self-selecting factors still find that several Asian groups out-perform whites in the economic domain. The most pronounced disparities are among women. In a comprehensive 2019 study conducted in Canada, researchers controlled for age, marital status, education level, and native language to compare yearly incomes between second generation ethnic groups with white Canadians. Interestingly, no second generation male ethnic group out-earned third-plus generation whites (without controlling for the aforementioned variables, South Asian, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese men out-earned third-plus generation whites). The outcomes among women, however, were very different. South Asian, Chinese, Southeast Asian, and Korean immigrant women all out-earned third-plus generation white women. The intersectional claim of overlapping oppression again fails because ethnic women perform relatively better than ethnic men compared to their gendered counterparts.